The following is a sermon given by Dr. Hulsey on Sunday, May 20, ahead of the annual “Senior Shake.”

This past February I was attending a headmaster’s meeting in Durham and found myself sitting next to the former headmaster at Episcopal High School. Rob Hershey retired from Episcopal two years ago, so I know him well. In fact, his first teaching position out of Williams College was at Woodberry, so he knows Woodberry well. I had on my Woodberry tie and explained to him that I would be leaving the meeting early in order to fly to New York for an alumni gathering that evening. Those of us who know Mr. Hershey know that he is fiercely competitive and that he rarely gives an inch, especially when it comes to his passion for Episcopal and his eagerness to take it to the Tigers whenever he can. But when I mentioned our alumni, Rob nodded, and after a pause said, “You know, Byron, I love Episcopal, but there’s no doubt that the Woodberry alumni love your school more.”

Now it’s impossible to measure exactly the love, devotion, commitment, and passion that an alumni community has for its school, and I understand that I’m about as biased as I could ever be, but I can’t imagine any school in the nation that is loved like Woodberry is loved by its alumni. I feel it everywhere I go: It comes through clearly in alumni stories about the unpredictable twists and turns of life on dorm, memories down the hill of games played in the freezing cold, early morning Saturday classes with quizzes and tests that no one thought they deserved, the primordial belief in the power of the bonfire, and the drudgery of Saturday night demerit hall. I remember visiting with an alumnus, now in his 80s, who was caught smoking at Woodberry without permission. He recalls that his punishment was to run 100 miles, and he still loves the school — maybe he even loves it more because of that formative experience. I feel the endurance of that love every April when teary-eyed alumni come back on campus and pick up with their friends exactly where they left off, five, ten, twenty, and fifty years ago.

I often ruminate on why the Woodberry alumni love the school as much as we do. Now I take it as a given that not every alumnus had a supremely positive experience and certainly not every single alumnus loves or even likes the school. And I’m very well aware of the fact that not every one of you loves the school and that a few of you have even decided that you won’t return next year. I get that, and yet I’m still struck by how deeply committed and emotional so many Woodberry alumni are about the Tiger Nation. As we anticipate this year’s Senior Shake, I thought I’d offer a few reasons why I believe the school is so deeply loved, and some thoughts about the graduating class and the legacy you’re leaving those of us who will return next year.

It’s the culture that matters most. We’ve never wavered from our mission as an all-boys, all-boarding school. The clarity of that institutional identity, coupled with our location and the beauty of this campus, combine to create extraordinary friendships and relationships with teachers and coaches and mentors that last a lifetime. Because we are all-boys, and all-boarding, each one of you is equal here, in ways you’ve never been before and may never be again. You stand shoulder to shoulder with each other. As equals, everyone’s held to the same high standard. Here you learn together, laugh together, suffer together, win together, and lose together. Here, when we’re at our best, we are one. We come from many places and many backgrounds, now from all over the world. We have wide-ranging and varied passions and interests in academics, athletics, and the arts, but because we are all-boys and all-boarding, and because we buy into the same high standards, we are one single, unassailable band of Tiger brothers.

Last spring in The New York Times, columnist and social critic David Brooks distinguished between thick and thin institutions. The wider national culture increasingly favors the whimsical, selfish preferences of the individual over the sustained power of community. Consequently, national institutions have grown thinner over time. But we’ve thickened here, especially in comparison to what we see in the world beyond. Because there are so few places like Woodberry left in the world, our alumni are more closely bonded to the school than they’ve ever been. Mr. Brooks writes that “a thick institution is not one that people use instrumentally, to get a degree or earn a salary. A thick institution becomes part of a person’s identity and engages the whole person: head, hands, heart, and soul. Thick institutions have a physical location, often cramped (think C-dorm), where members meet face to face on a regular basis, like a dinner table or a packed gym or assembly hall.”

He goes on to write that “such institutions have a set of collective rituals — fasting or reciting or standing in formation. They have shared tasks, which often involve members closely watching one another, the way hockey teammates have to observe everybody on the ice. In such institutions people occasionally sleep overnight in the same retreat center or facility, so that everybody can see each other’s real self, before makeup and after dinner. Such organizations often tell and retell a sacred origin story about themselves. Many experienced a moment when they nearly failed, and they celebrate the heroes who pulled them from the brink. They incorporate music into daily life, because it is hard not to become bonded with someone you have sung and danced with.”

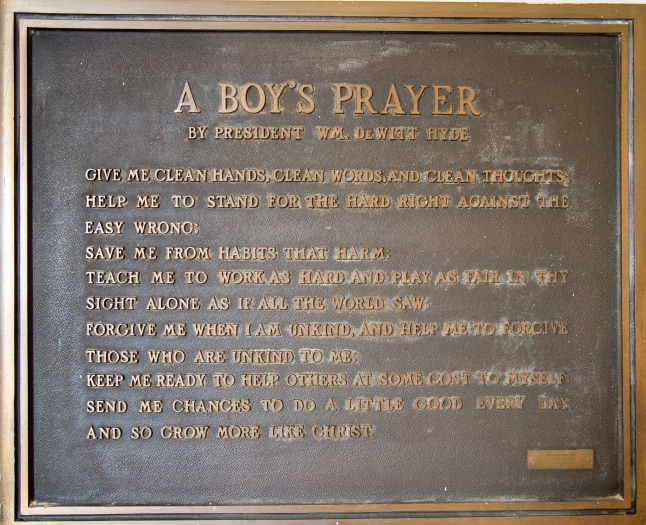

As social creatures who crave belonging, we feel emotionally about thick institutions like Woodberry. These kinds of communities seep into us and shape us. In a sense, thick institutions and strong communities tweak our social DNA, often for the good. One bedrock element of the school’s culture is our longstanding, unwavering commitment to seeking truth. The value that we’ve placed on the truth resonates with Woodberry alumni from every generation. Too many in the world beyond have a shaky allegiance to the truth. They pick and choose only the facts that support their view, or, even worse, they ignore the truth altogether and live in a made-up world that aligns with their preferences rather than the truth that binds a place like Woodberry together. In Paul’s second letter to Timothy we learn that these charlatans “will gather around them a great number of teachers to say what their itching ears want to hear. They will turn their ears away from the truth and turn aside to myths.”

The commitment to truth runs deeply through our academic lives here: Your science teachers demand that you generate, assemble, and communicate data to advance a hypothesis that you’ve posed; your math teachers often insist that you show the work that yielded an answer; history and English teachers require that you support your opinions with historical facts and references to the text. The truth matters here — it always has and it always will. Over time a boy learns here that the truth liberates him to be his best self, as opposed to being chained to a fake self in an unreal, fabricated, even dystopian world.

Truth, of course, is the essence of the student-run honor system, and it’s foundational to our common commitment to ourselves and each other that we’ll tell the truth, complete our own academic work, and respect what belongs to others. When we practice a reverence for the truth we present our best and most noble selves, and that standard has bonded generations of Woodberry alumni. We benefit here from a standard that we inherited, one that sends a message near and far that a Woodberry alumnus is a man of honor and integrity. Jameel Wilson’s father, Alfred, told me a story last year about closing a business deal. At the very end everything was stymied and progress had slowed to a crawl. Then the attorney from the other side, the father of an alumnus, called up and said, “Our sons are Woodberry boys. I know what you believe and we’re gonna get this deal done.” That’s the power of trust that comes from an unwavering devotion to the truth.

A commitment to the truth also demands that we understand that life at Woodberry is full of disappointment and even failure. If you’re going to be a Woodberry boy, you will be roughed up and bounced around, and it’s in these moments that you’re faced with an opportunity to grow through the disappointment to reach higher than you could have reached if you’d never failed in the first place. This year’s senior prefect captured it beautifully when he shared with me that “the only way to succeed is to become comfortable with failure.” If you’re devoted to the truth, you can’t run and you can’t hide.

Truth flows through our social relationships and our friendships at Woodberry, too. A sixth former shared with me earlier this winter that “you have to be yourself” if you’re going to make it here. In our community you can’t fake it and hope to escape the poking and prodding and occasional ridicule that comes with trying to be someone you’re not. I recently shared this observation with an alumnus from the class of 1985, and he said, “That’s exactly why I love Woodberry so much. You have to learn to stand up for who you are, and if you do, your classmates will love you forever.” The Woodberry experience offers each of us multiple avenues for self-discovery. The place has the power to reveal who we are, full of strengths and weaknesses, and–when we’re at our best–accepting of each other and full of hope that tomorrow each of us will be a little better than today.

129 years. 106 in this chapel. It’s obvious that we inherited the culture that we enjoy today. Woodberry’s culture is an extraordinary blessing, an underserved gift, one that has elevated my life, and I hope yours, too. Clearly we should be grateful. But God calls on us to be more than mere inheritors; we are creators, too. In our fleeting time, each one of us is faced with daily opportunities to restore and renew and revitalize Woodberry’s culture, just as each one of us can fritter those moments away and let the place grow stale and warped and ossified. In closing, I want to pay tribute to the class of 2018 and the legacy of brotherly camaraderie you have grafted onto the culture here.

More than any other class I’ve known, you’ve practiced what it means to take care of each other. By the way, not a single one of us is perfect in this regard. We all have regrets of missed opportunities to save a friend or advisee or student, but if the truth is told, you answered the call forthrightly and bravely. You’ve taken on the responsibility of reaching out to help one another. This has happened consistently, in ways both small and large, ways that are seen and unseen. It’s an element of the climate here and it matters. One sixth former compared Woodberry to his old school and said, “Here we pull for one another.” He didn’t get that at home. Perhaps even more to the point, it hasn’t always been that way here at Woodberry. But you’ve done your part to make this place better. You pull for one another, on stage, on the court, in the classroom, as peer tutors working with younger boys, and on dorm talking with a friend who needs the presence of your companionship.

Small actions mean more than you might think. It’s when older boys pair up with alumni and judge the physics fights for third formers on the last Sunday of the school year for seniors. It’s when a prefect or a defect or an old boy from home checks in on a boy who’s homesick just to lend a hand. It’s when the hulking Edward Solms picked up the decidedly smaller Daniel Vroon on the second Saturday in November and apologized for not winning the game in Daniel’s new boy year. It’s a cheerleading crew that is more uniformly positive and enthusiastic. It’s a senior class that organized two student-only assemblies this year, the first to address the problem of theft and to restore our community of trust, and the second to take responsibility for making healthy decisions and to rid our campus of nicotine and drugs.

Your legacy won’t be state championships or numbers of Walker Scholars. Along the way, like every class in Woodberry’s history, you’ve stumbled and been bloodied and fallen short. The crooked places have not all been made straight. But it’s been a privilege to watch you grow through the school and I want you to know that I’m grateful for the ways you’ve taken care of each other. When it comes to well-rounded excellence and meaningful contributions to your classmates and the younger boys, you’ve enriched our culture.

Culture matters most, and at a place like Woodberry, culture often evolves slowly, even imperceptibly. But on occasion there is a group of leaders, some known and others unknown, who step up and step forward to make an enduring contribution. You’ve left those who will return next year an extraordinary opportunity to sustain what you started. Your legacy is a challenge for future classes to make Woodberry an even stronger school going forward, a place where every boy learns to work hard, build his character, and like the class of 2018, take care of each other.

The following is a sermon given by Headmaster Byron Hulsey during the first chapel service of 2017.

The following is a sermon given by Headmaster Byron Hulsey during the first chapel service of 2017.