The Eulogy for Sam Byron Hulsey was given by Byron Hulsey on August 6, 2020, at the Trinity Episcopal Church in Fort Worth, TX.

On behalf of Isabelle, Ashley, Marc, Ben, and Claire, I want to thank you for joining us this morning as we give thanks to God for Sam’s extraordinary life and we share together as one body the sadness and the grief that comes with saying goodbye. I want to thank Father Pace and his staff at Trinity for graciously and generously hosting us and putting up with what must seem like an endless array of requests and questions. Some of you know that Sam annually revised his extensive and detail-laden funeral plans every Ash Wednesday. I thought the practice was a little morbid, but he was a planner, and goodness knows, we’ve had a year to get prepared for today’s service.

Sam shaped for himself a beautifully integrated life. He was at home everywhere, and there was no separation between his personal life and his professional life and no separation between how he treated the many men and women in his life. An ardent and lifelong admirer of the Royal Family, Sam would get up early to watch every minute of a royal wedding or royal funeral. He was delighted to meet the Queen and Prince Philip at Buckingham Palace as part of the House of Bishops’ Lambeth meeting. And he was just as happy at the Malt Shop on highway 180 east of Weatherford or catching up with Mary Meredith, who cut his hair every four weeks for eighteen years when we lived in Lubbock, or connecting every morning with Neva at the Periwinkle gift shop on Deer Isle in Maine. He loved the ritziest restaurants in Manhattan and the newest exhibition at the Modern Museum of Art and he has lots of fun at the Weatherford rodeo. He was a fan of the valet service for his Cadillac at Rivercrest, and he got just as much joy out of a Meals on Wheels run with cousin Judy and gardening with Oscar at Selby Hill or going to see Jerry Jeff Walker at Billy Bob’s just after Christmas. He enjoyed the full regalia and the polished array of accoutrements like the pectoral cross and the fancy purple ring that came with being bishop, and he was just as happy in his raggedy pajamas in the early morning at Selby Hill hauling out corn for the deer and seed for the birds.

Sam was a passionate reader and hand-wrote tens of thousands of notes and letters to people all over the world. He was a devotee of Thomas Merton and Carl Jung and Richard Rohr and Wendell Berry. And he faithfully read scores of hastily published and, to be truthful, monotonous church bulletins from all over the country. “Put me on your mailing list,” he’d say. Sam needed the print copy of the daily New York Times like most of us need early morning caffeine or a healthy breakfast to start the day. No other paper would satisfy him. He was snobby about his reading, and at the same time he devoured every issue of the Canadien Record from Northwest Texas. Sam subscribed to the New Yorker, and, without even a trace of shame or irony, to People magazine. He loved the opera in Fort Worth, and once he took my wife, Jennifer, to see “White Chicks” at the Weatherford Cinema. They giggled and giggled at what he described as the “nastiness.” One of Sam’s defining qualities was that he was high brow, middle brow, and low brow all at once. That one exceptional gift resulted in a genuine friend list longer than anyone I’ve ever known. His hospice nurse, Cheryl, texted me the day Sam died and wrote, “He was my best friend and I am really going to miss him. He gave me so much good advice and joy. It’s like losing my dad all over again.”

I’m not sure anyone knew Sam better than our mother, Linda. They were a team. She boosted him up when the parishioners dragged him down, and she kept him grounded when his ego got a little carried away. I once found a folder from his yearly Advent trips to Weston Priory in Vermont. She’d go with him, and as they drove away after the week-long retreat, they’d talk and she or he would take notes on all the monks they met and all the details from their lives. Then he’d go over that folder every year just before the next trip so that he was ready to pick up where he’d left off.

Early in their marriage, Mom and Dad were flying to LaGuardia for a big trip to New York City. Mom was seated on the aisle, Dad in his clerical collar in the middle, and a very attractive young woman on the window. He immediately began visiting with her, much to Mom’s irritation. They chatted and chatted the whole way, while Mom read a book or pretended to nap. Upon the descent, the plane ran into turbulence and the passengers were anxious, bouncing around uncomfortably. At one particular point, the woman on the aisle grabbed Dad’s wrist and said, “Father, please pray for us.” Mom leaned forward and made her first and only contribution to the conversation: “It’s not going to do you a damn bit of good.” Sam gently pushed back, “Well, Linda, it might.” Sam and Linda were good for each other.

When Mom was stricken with Alzheimers, she depended on Dad for almost everything and he delivered. One day he took her to get her hair done, but a trip like that with Dad always turned into countless stops to the post office and then to friends and acquaintances who might need a quick visit or be interested in a book or a cut-out article from the newspaper. On and on the morning dragged, and Mom was getting more and more agitated. She just wanted to go home. After chatting with someone on the front porch, Sam came bounding back to the car, climbed in, fastened his seat belt, but before he could crank up the car, Mom, even in her depleted state, came forth with a zinger: “Who do you think you are, Jesus’ little friend?” Taken aback, Sam recovered and said, “Well, yes, Linda. That’s exactly who I am.”

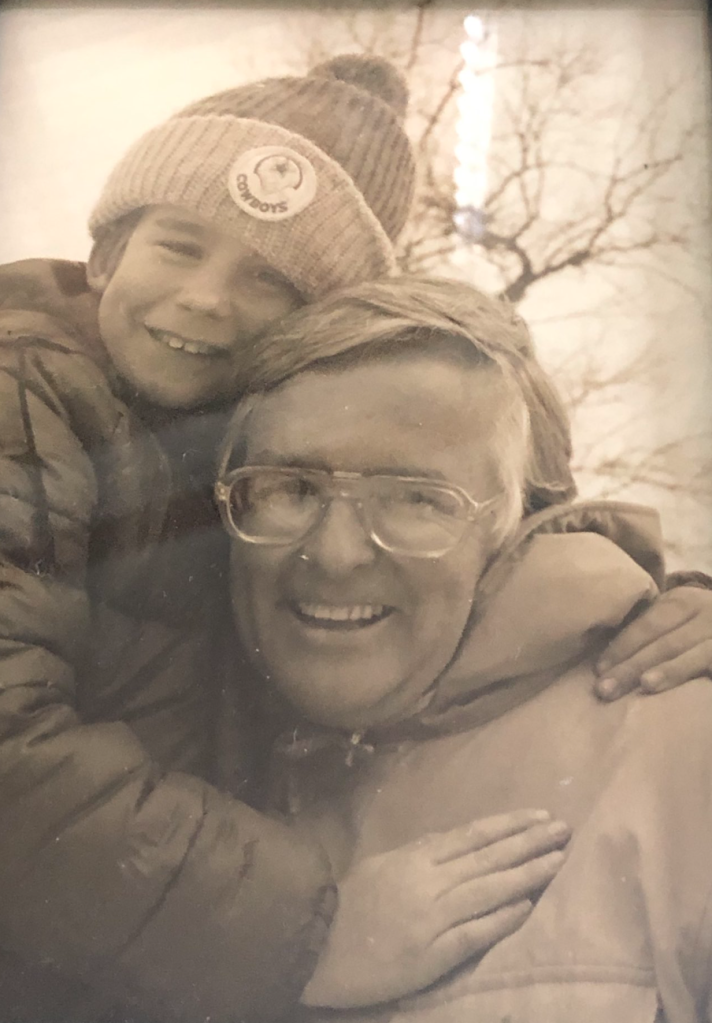

Part of being Jesus’ little friend was accepting and loving and celebrating all of us for who we are, not trying to turn any one of us into who he might otherwise want us to be. This completely authentic belief animated his early support for women to serve as priests in the Episcopal Church and the wide-ranging progressive beliefs that ran counter to more conservative doctrine. Sam treasured the servant-leadership style of the good shepherd, and in confirmation sermons he would tell the confirmands that Jesus’ great command was to “follow me,” not “obey me.” I remember once when I was six or seven that Ashley upset me over this or that nonsense. I may have been crying. Sam said definitively and lovingly, “Be careful with Byron. He is sensitive.” This was the 1970s, and the established culture conditioned dads to teach their sons to be tough and stoic and push down their feelings. But Sam made clear that sensitivity in a boy is a gift to be nurtured, not a disability of which to be ashamed. Ashley’s a really good person, so I don’t know if she needed to hear what he said in that moment, but as Sam’s son, I needed to hear that in my momentary fragility, I was ok and that I was loved. As a father, Dad modeled as close a manifestation of unconditional love as Ashley and I have ever known.

Sam told me just over a year ago that he had seventeen godchildren. I bet there are closer to one hundred or more who think of him as their godfather. It’s because he knew us and he loved us and affirmed our gifts in hand-written notes, quick phone calls, and long car trips through Northwest Texas. I’d love to know how many men and women he married. In his homilies, he’d often quote Thomas Merton: “The beginning of love is to let those we love be perfectly themselves, and not to twist them to fit our own image. Otherwise we love only the reflection of ourselves we find in them.”

Because the world, and even his beloved Episcopal church, is often disintegrated and broken and separated and bifurcated into either/or dichotomies, Sam’s integrated life gave him a lot of pain. It’s pain that he embraced as the necessary cost of living a good life. He saw our son, Ben, as a soulmate, and it mystified Jennifer as a young mother when Sam once said, “Oh, how I love Ben. And he’s going to have a lot of pain.” What he meant was that a good life comes with pain and when we walk into the world’s pain in service to others, we live a good life.

The last time we saw Sam was in July 2020 at Selby Hill. We had no idea he’d die less than three weeks later, but because of COVID and his cancer we knew it was likely the last time we’d see him. Saying goodbye was brutal. We were out at the car for the farewell. Claire gave him a big hug. We all did. And then Claire needed more, so she went back for one more hug. He told her with complete conviction, “Claire, always remember that I am on your team.” Sam’s gift to us was to make it clear that he was on the team of everyone here and everyone he knew and loved. That’s why we miss him.

The evening Sam died, Jennifer went to bed early and I checked in on Claire. We were both teary and I asked if she needed any help getting to sleep. She said no and gave me a hug and said through her tears, “Dad, I’ll always be on Sam’s team.” Claire got the message, and given what our broken world needs, I hope that we might all seek to be on Sam’s team, too. Amen.